Yesterday a smaller sized blog on a recent addition, but this time you have to do more of an effort to learn something on this artist. Here is the text by Aaron Schuster on Gabriel Lester

More is Lester

On the cinematic in the work of Gabriel Lester

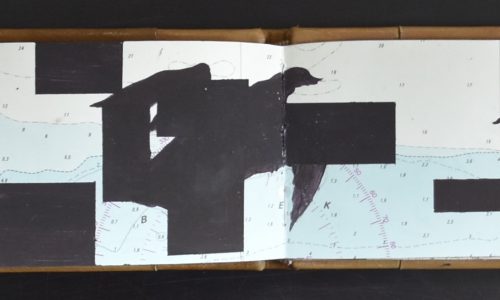

My title is in part inspired by a particularly felicitous slip of the tongue made during a lecture I attended in Brussels on the films of Marcel Broodthaers. The speaker, wishing to express the great economy of Broodthaers’s productions, often made with meager means, presented the principle of his work as follows: Comment faire un minimum avec un maximum, or, as one would say in English, how to do less with more… Of course, this ‘error’ is much more revealing of – in this case, not the speaker’s secret intention but – the actual situation, the essential wager, of contemporary art, especially in its relation to mass culture. Put simply, the problem today is not so much maximizing scant resources or creating the greatest effect with relatively little means (think of the typical artist’s production budget compared with that of a Hollywood blockbuster), but how to introduce a cut or absence in the massive ballast of already existing things. How to do ‘less’ with the ‘more’ of the world, or, if I can be forgiven this pun, how to lester it. According to the Jewish doctrine of Tsimtsum, God created the world via a movement of self-contraction: in order for the world to emerge God first of all had to withdraw a part of Himself, to give up some of His all-encompassing Being, lest there be no space for anything to come into existence whatsoever. Far from the world miraculously emerging from the void, the void itself is something to be actively produced. What is fascinating about this mystical ontology is the way it puts negation at the very heart of creation. The emergence of something new depends on the preliminary work of clearing away, of carving out a space in a universe that is already supersaturated, too full, too present, too much – the birth pangs of the new correspond precisely to the difficulty of this negative labor. This particular understanding of the creative act has not escaped the attention of artists and philosophers. Indeed, two of the most famous artistic pronouncements of modern times, Mallarm√©’s “Destruction was my Beatrice,” and Picasso’s “A picture is a sum of destructions,” point precisely to such a subtractive aesthetic. Gilles Deleuze’s definition of painting is here exemplary: “the painter’s problem is not how to enter into the canvas… but how to get out of it.” (1) What does he mean by this? Before any pigment has touched the painting’s surface, the canvas in a way already contains “everything [the artist] has in his head or around him,” (2) an amalgam of vague images, possibilities and visual clichés, so that the task of painting is to cut a path through the chaos. (Balzac’s story “The Unknown Masterpiece,” one of the great programmatic texts of artistic modernity, spells out the dire consequences for the artist unable to find his way out of the canvas…) Along similar lines, in her description of the writing process Marguerite Duras states, “What you’re going to write is already there in the darkness.” Before the work of writing proper, a ‘pre-written’ text of amorphous ideas, half-formed phrases, and habitual formulas is already swirling about in the writer’s head, a kind of “black block” that must be broken up, pulverized if the sentences and paragraphs of the written piece are to take shape and become legible. “I’m in the middle, and I seize the mass that’s already there, move it about, smash it up – it’s almost a question of muscles, of physical dexterity.” (3) To grasp what is at stake in this process, one needs to reverse that humdrum metaphysics which defines creation in terms of addition or filling in a void; on the contrary, the artist begins with an excess and his work is that of smashing up, stripping away, cutting through, getting out. All artists are escape artists.

In the case of Gabriel Lester, the kind of cutting involved in his work is paradigmatically cinematic. That Lester’s work is intimately connected with film has often been noted, and the artist himself has evinced some interest as a filmmaker in his video pieces. Travel Without A Course (2004), for example, offers a kind of ‘portrait of the artist as a young screenwriter’, narrating an autobiographical journey to ex-Soviet Georgia where Lester intended to hole up with an old typewriter and knock out a script. The string of wayward encounters that follows recalls the meandering character of another video, All Wrong (2005). This short movie recounts the exploits of what is known in the psychoanalytic literature as a ‘normal psychotic’, a perfectly well-adapted person who floats through life without any inner psychological core, an actor with no existence outside his roles. The piece is remarkable for its novel use of the now standard practices of sampling and remixing: all the images in the video were found on the internet via various search engines and later edited together to illustrate the story. Here form and content go together, the amoral adventures of the movie’s main character imitating the aleatory wanderings of the typical internet surfer. Beyond these more overt video experiments, however, it is primarily the installations that address the question of the nature of cinema, breaking down and re-deploying its different constituent elements and techniques. Unlike many contemporary artists who use film as the starting point for their practice, re-cutting existing movies, replaying them under modified conditions, making videos in the margins of classic films, and so on, Lester works on a much more formal level. For him film is not a given material to be manipulated, a privileged part of the daily spectacle, but first and foremost a way of seeing. Indeed, Lester’s installation work might well be considered a post-cinematic art, that is, an art that has been shaped and formed by a distinctly filmic kind of perception, one made by a film-lover who has grown up with the movies.

How To Act (2000), Lester’s first and arguably still most visually impressive installation, described by the artist as a “dramatic light edit,” treats projected light as an autonomous element with its own rhythms and configurations. The effect of the piece is akin to seeing the luminous patterns and random flashes emitted by a TV set in a dark room; without knowing what images they correspond to, the dance of lights takes on a life of its own. How To Act presents a kind of zero-degree cinema, doing away with the ‘moving picture’ or film qua imaged story. What remains is the flicker of the screen, accompanied by soundtracks taken from old VHS tapes, now calibrated and choreographed as an independent work. Through this reduction the installation provides a kind of anamorphotic view on the movies, a look unable to make out the figures on the silver screen but entranced by the abstract light blobs that they are. Habitat Sequences (2000) plays as well with the possibilities of lighting, this time in relation to a fixed set whose physiognomy radically changes as it is differently lit. A standard living room appears like a crime scene in some hardboiled detective story or the setting for a lovers’ tryst as strategically positioned lamps switch on and off, revealing multiple and sometimes contradictory surroundings: a cozy corner here, a menacing emptiness there, a phone about to ring with an urgent message, a washed out overview, a tiny light burning in the darkness. There is definitely something cold and calculated about this work, almost mathematical in its precision, as it enumerates the possible permutations of mood and feeling enabled by alternate lightings. Rosemary’s Baby (2002) achieves a similar ‘sequencing’ effect though without the use of lights. A room is sealed off, inaccessible to the spectator, save for cuts in the walls that permit six different views into its interior. Lester’s reference is to the mysterious second apartment in Polanski’s film, behind Mia Farrow and John Cassavetes’s, where the satanic intrigues take place. Just as the space of this apartment is hinted at throughout the movie yet always partially out-of-frame, so too can Lester’s room only be peeped into. The voyeurism is heightened by the room’s disheveled d√©cor, looking as if ransacked by a burglar or wrecked in a domestic dispute: someone has been here before. Altar (2001) and Cross Section (2006) employ the same cutting technique, the former consisting of a pub divided by wooden sheets into separate lanes, the latter a building with slices take out of it allowing for different peeks inside its network of rooms and corridors. Lester cuts a room as if it were a film, and many of his installation works can be conceived as spatial edits, introducing temporal movement to an otherwise fixed or static environment.

In one of his essays André Bazin argued for a “mixed” cinema, that is, for a cinema that would be enriched by its borrowings from the other arts. (4) Alain Badiou, taking up and radicalizing this thesis, describes cinema as “an impure art,” “the ‘plus-one’ of the arts, both parasitic and inconsistent.” (5) For Badiou cinema is an inherently hybrid medium, taking from theater, literature, music, painting, and so on, without having a ‘proper’ domain. “Cinema is the seventh art in a very particular sense. It does not add itself to the other six while remaining on the same level as them. Rather, its implies them […] It operates on the other arts, using them as its starting point, in a movement that subtracts them from themselves.” (6) What is unique to cinema is the way that it mobilizes the different arts so that they become contaminated with one another, thus creating an impure, heterogeneous space: a supplement or a ‘plus-one’, not a Gesamtkunstwerk-style synthesis. What Lester does is retranslate the impurity characteristic of cinema back into the realm of the plastic arts. His installations isolate and examine different component elements of film like lighting, set design, music, and image, while subjecting them to a cinematic treatment (cutting, multiple takes, frame/out-of-frame tension, etc.). In my mind, the two works that best exemplify this technique are Clock & Clockwork (2003) and Highlight (plan B) (2004). The first involves a modish waiting room with a rotating wall – an old horror movie trick – that opens onto an eerily antiseptic clinical setting, a labyrinth of waist high tables with glass and metal partitions. The installation’s menacing yet pristine aesthetics is an homage, according to the artist, to Kafka and Cronenberg. The two versions of the waiting room (one brightly lit with a white cubical bookcase, the other with softer yellow lighting and chic wooden armoire) explore in a way similar to Habitat Sequences the effects of lighting on the creation of a space. Even more than the latter, Clock & Clockwork feels like a virtual movie set, the backdrop for an imaginary, non-existent film, with small objects placed on the immaculate laboratory tables – a sponge, a pencil – suggesting elements of a story that remains untold. Following a certain modernist logic, Lester’s installations evoke a hole or an absence, a missing film, an unknown narrative, a mystery figure, multiple perspectives that don’t add up. If Clock & Clockwork conjures a quasi-cinematic atmosphere, Highlight (plan B) deals with the cinematic apparatus itself. The viewer was first stuck by the impressive appearance of the object in the main hall of Brussels’s Palais des Beaux Arts: a cantankerous yet sleekly designed white machine, consisting of a large L-shaped support with multiple rectangular tubes jutting out the front. The tubes function as periscopes, cutting up reality on the other side of the machine into small viewable chunks and vertically displacing them via a system of meticulously calibrated tilted mirrors. You bend down and peer into the screen at your feet to see the designs on the ceiling; at eye level you view the tiles on the floor. (This inverted universe of mirror reflections is also reflected in the thin mirror strips that Lester discreetly attached to the sides of the columns in the hall). An escape artist is above all an illusionist, a trickster like Houdini, and here Lester’s funky contraption charms his audience even though its trickery is perfectly transparent. What is especially remarkable about Highlight (plan B) is the contrast between the elegance and simplicity of its visual illusion and the massive presence (even ugliness) of the technical apparatus needed to produce it – so great a device for such a rudimentary trick! It is as if the material correlate of the transformation of the real into images was this huge stain in reality itself. This is, of course, highly ironical, since today the means of technological reproduction have shrunk to tiny, pocketable proportions, while the capacity for image manipulation has become nearly infinite.

The Gabriel Lester publication is available at www.ftn-books.com