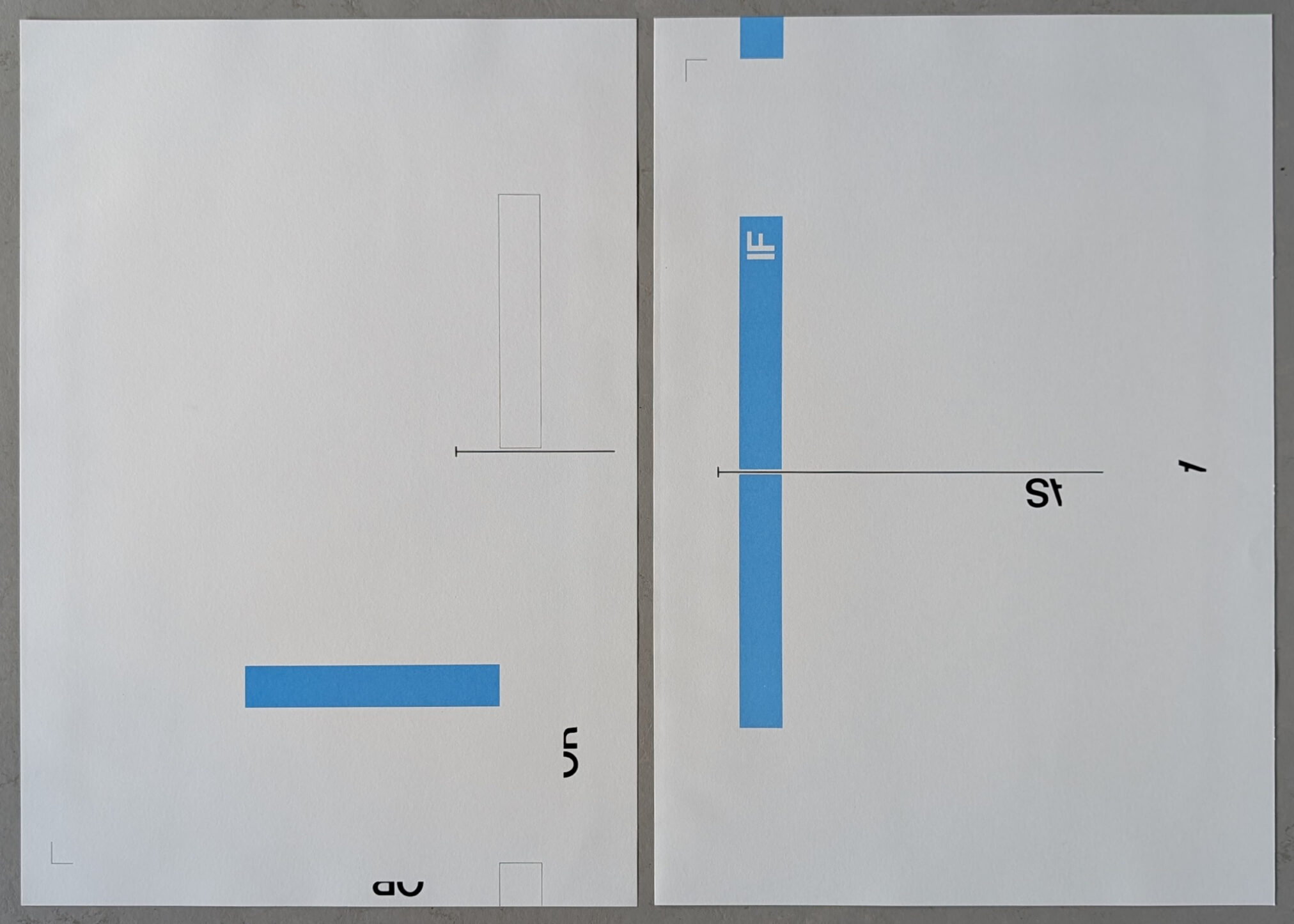

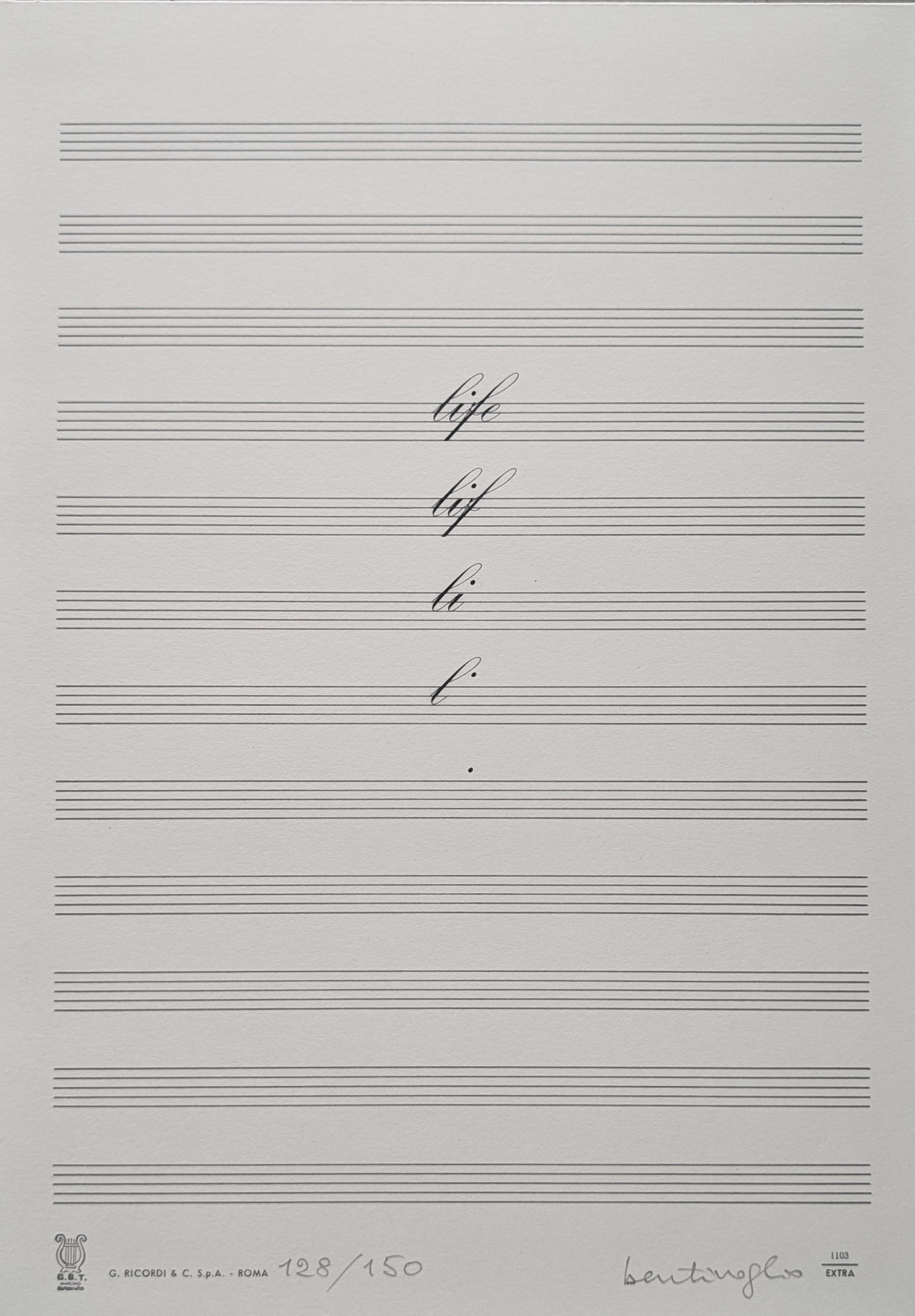

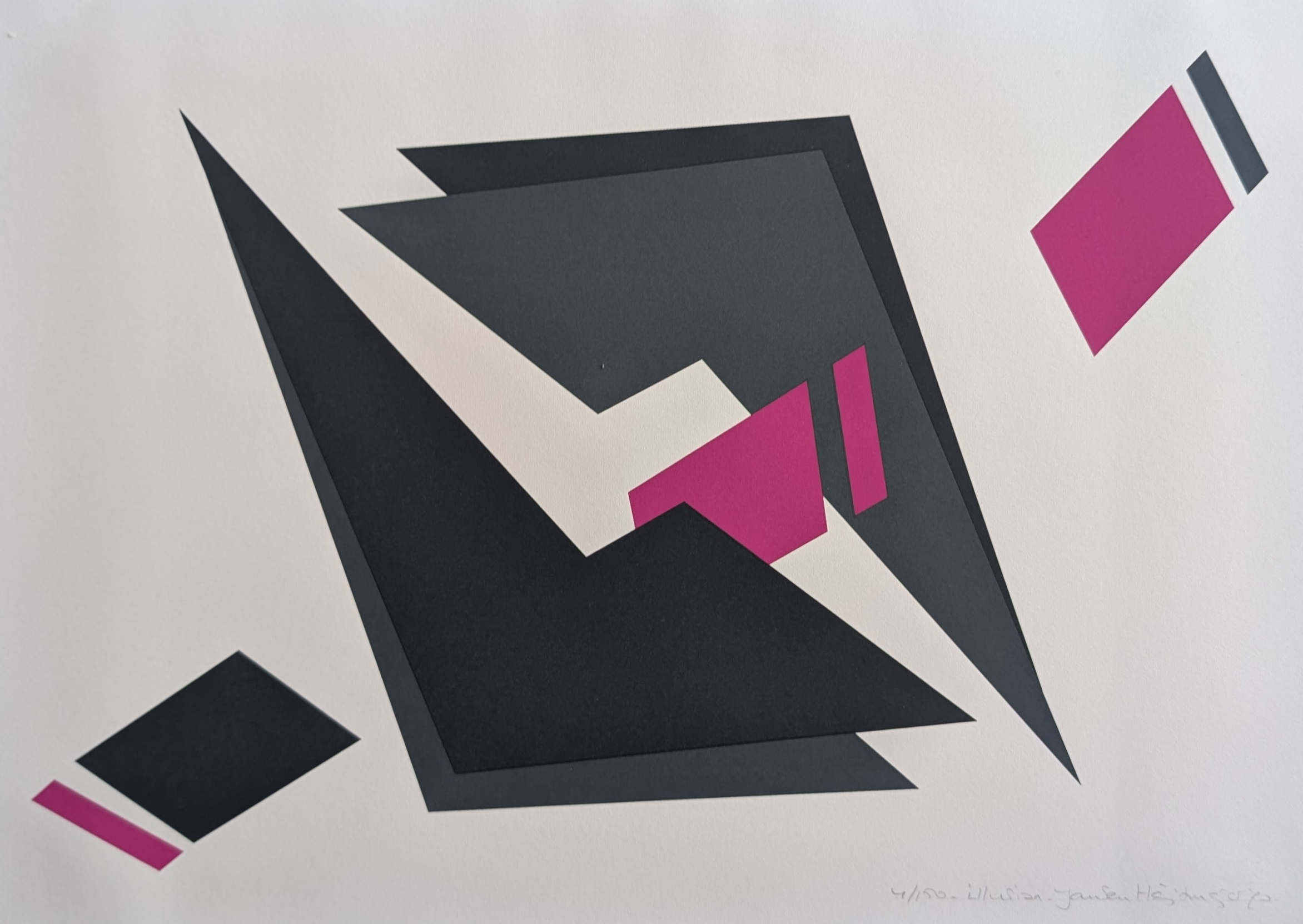

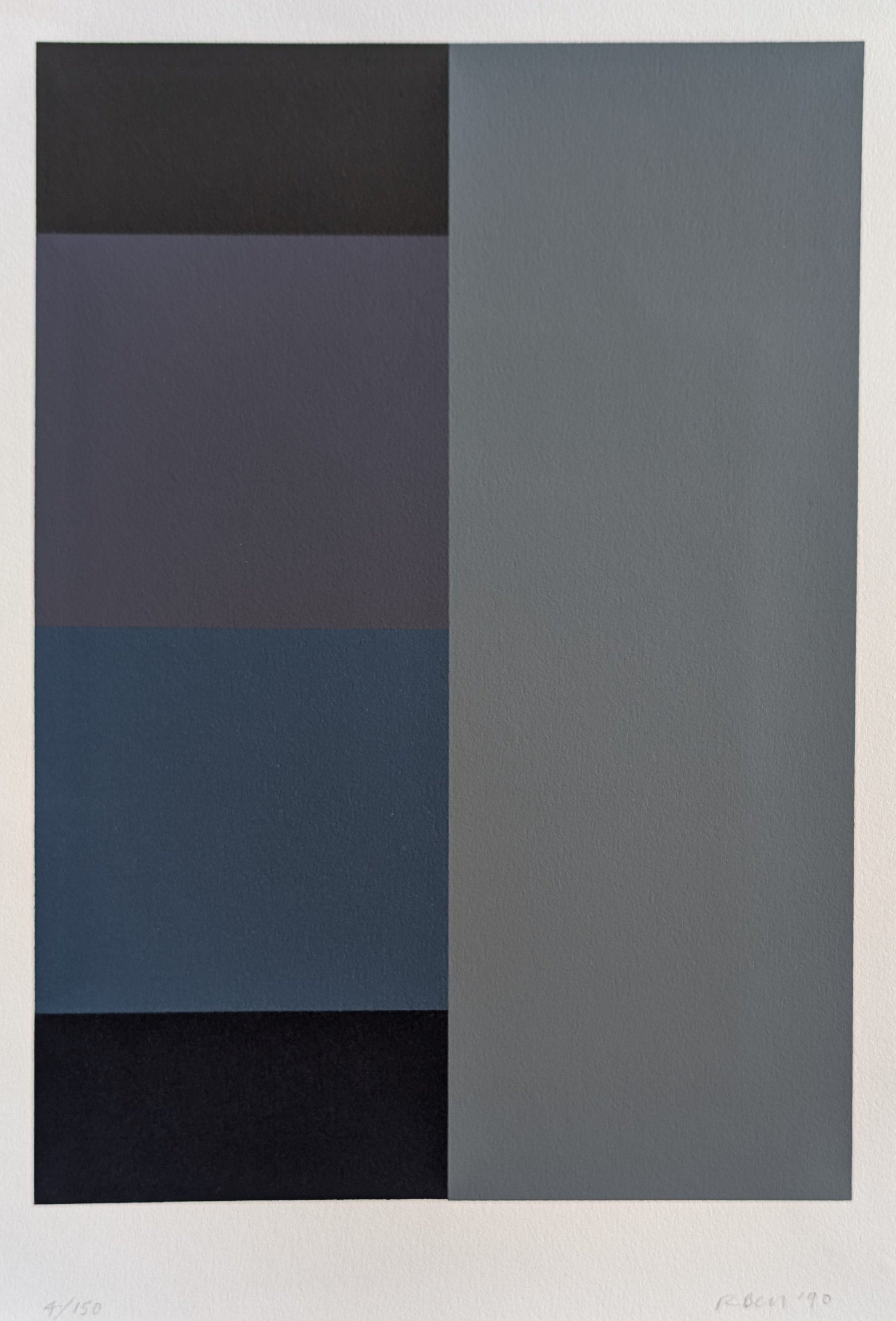

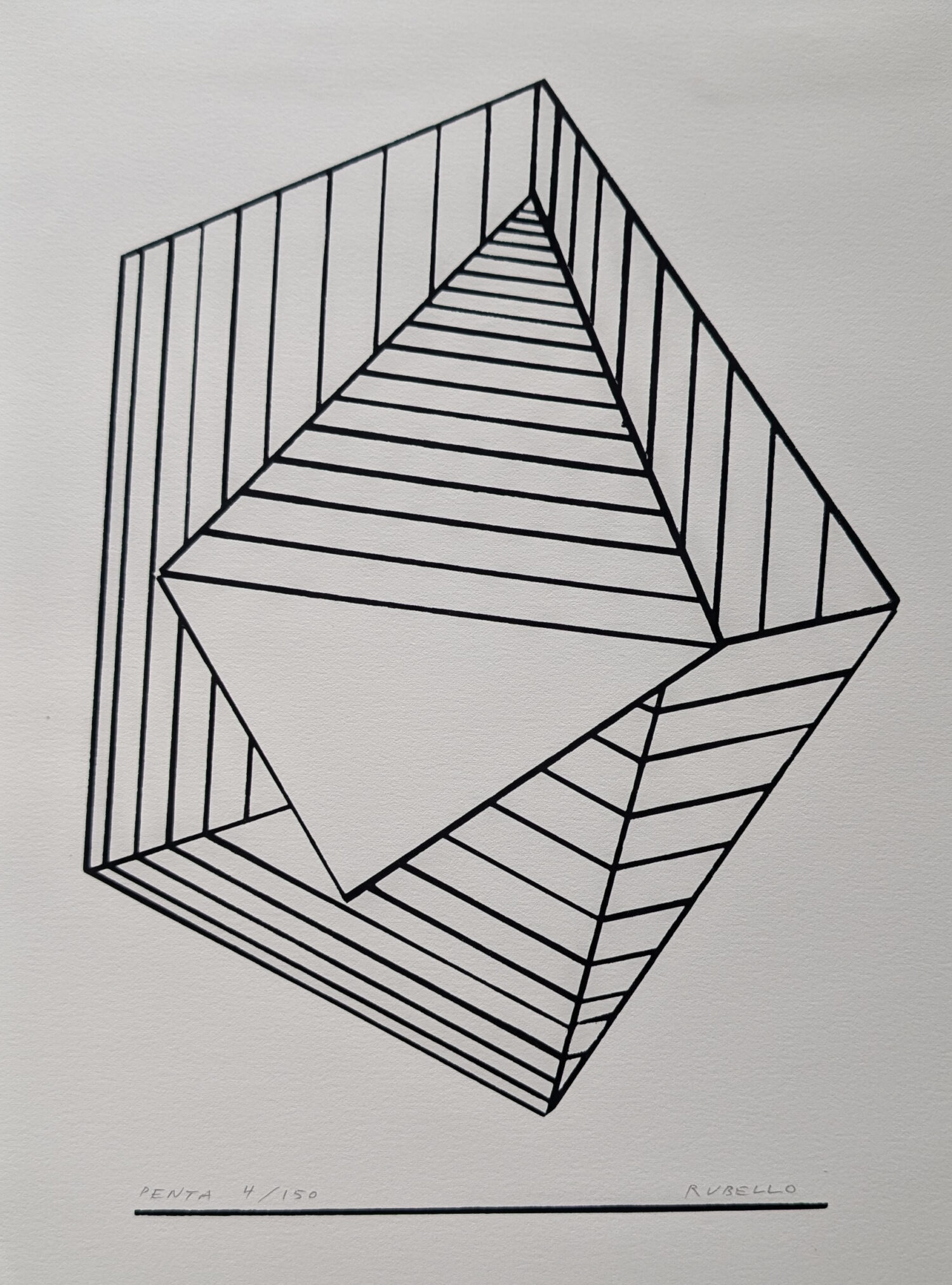

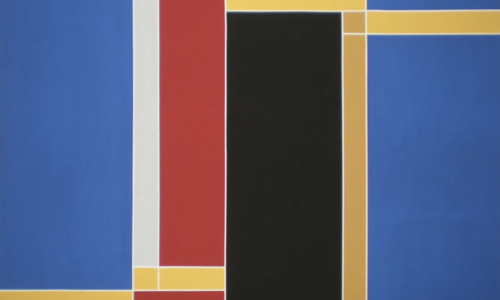

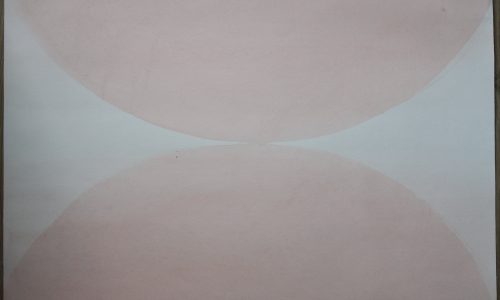

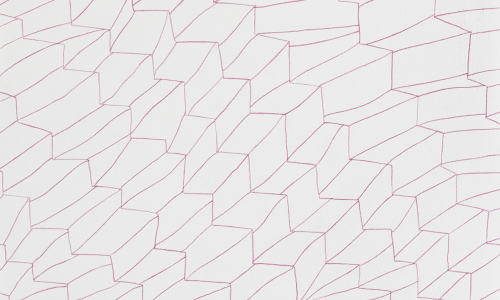

A professional artist, Downsbrough honed his craft with a keen focus on the fundamental elements of architecture: lines, planes, and the relationship between spaces and the meanings they embody. His work was characterized by its simplicity and precision, utilizing minimal forms often created with black tape or painted lines to prompt viewers to reconsider their perception of space. He also explored the power of language in his art, strategically placing words and phrases in different, sometimes unexpected locations to elicit new interpretations and dialogues.

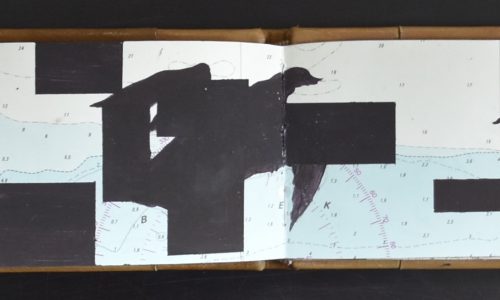

Downsbrough exhibited his work in both the United States and Europe, where he resided since 1989. His work has found a home in prominent museum collections, including the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the S.M.A.K. in Ghent. He was also renowned for his artist books, using text and line to create a dialogue between the physicality of the book and the conceptual space it offered.

www.ftn-books.com has several Downsbrough items for sale.