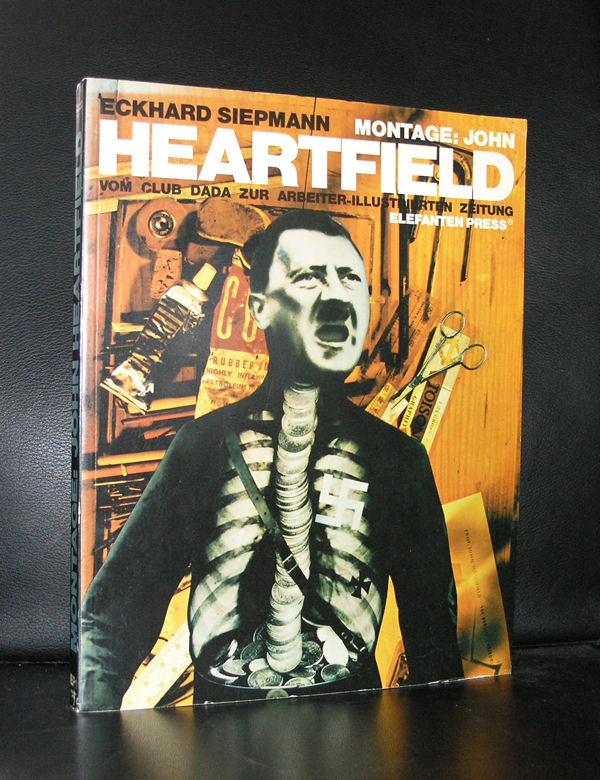

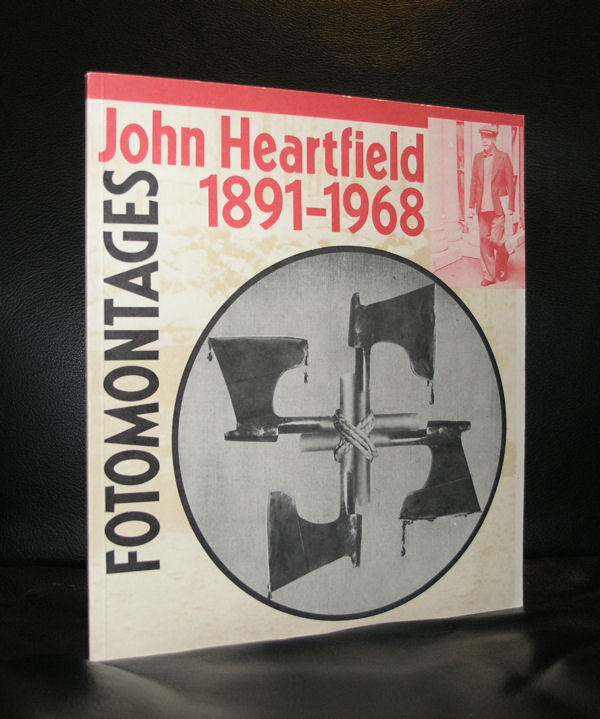

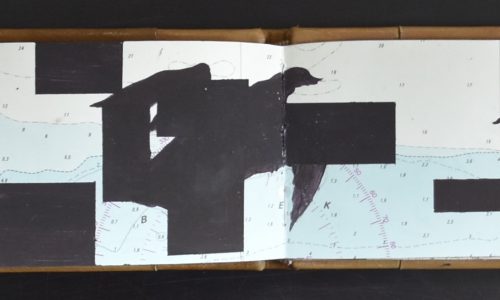

Not only does Heartfield manage to evade military service through a feigned psychological disorder, shortly thereafter, as German zeppelins sow bombs and fear over London, he protests by permanently exchanging his birth name Hellmuth Herzfeld for John Heartfield. In 1916, he meets like-minded artist George Grosz. At that time, Heartfield – trained at academies in Munich and Charlottenburg – is still working on landscapes. He burns them. His first considered photomontage is created a year later. At the bottom of the image lies a mutilated soldier, his battered body barely distinguishable from the earth of the battlefield. Above, a carpet of dead bodies stretches to the lead-gray horizon. In the narrow white strip in the middle, inscribed in his own handwriting, reads: This is what hero’s death looks like.

Together with Grosz, Heartfield is involved in the founding of the Berlin Club Dada, in which artists unite in response to the horrors of the war. Their absurdism and nihilism are directed against the prevailing values in the art world, but also against society. For Grosz and Heartfield, Dada is just the beginning. In 1918, they join the newly formed Communist Party of Germany, for which Heartfield creates a legendary election poster ten years later with a simple but effective photograph of the hand of a worker reaching out to grasp the viewer. His communist beliefs are also reflected in the way he works. Using mass media, he prefers to work as a laborer in overalls. And do not call him an artist, but a photomonteur.

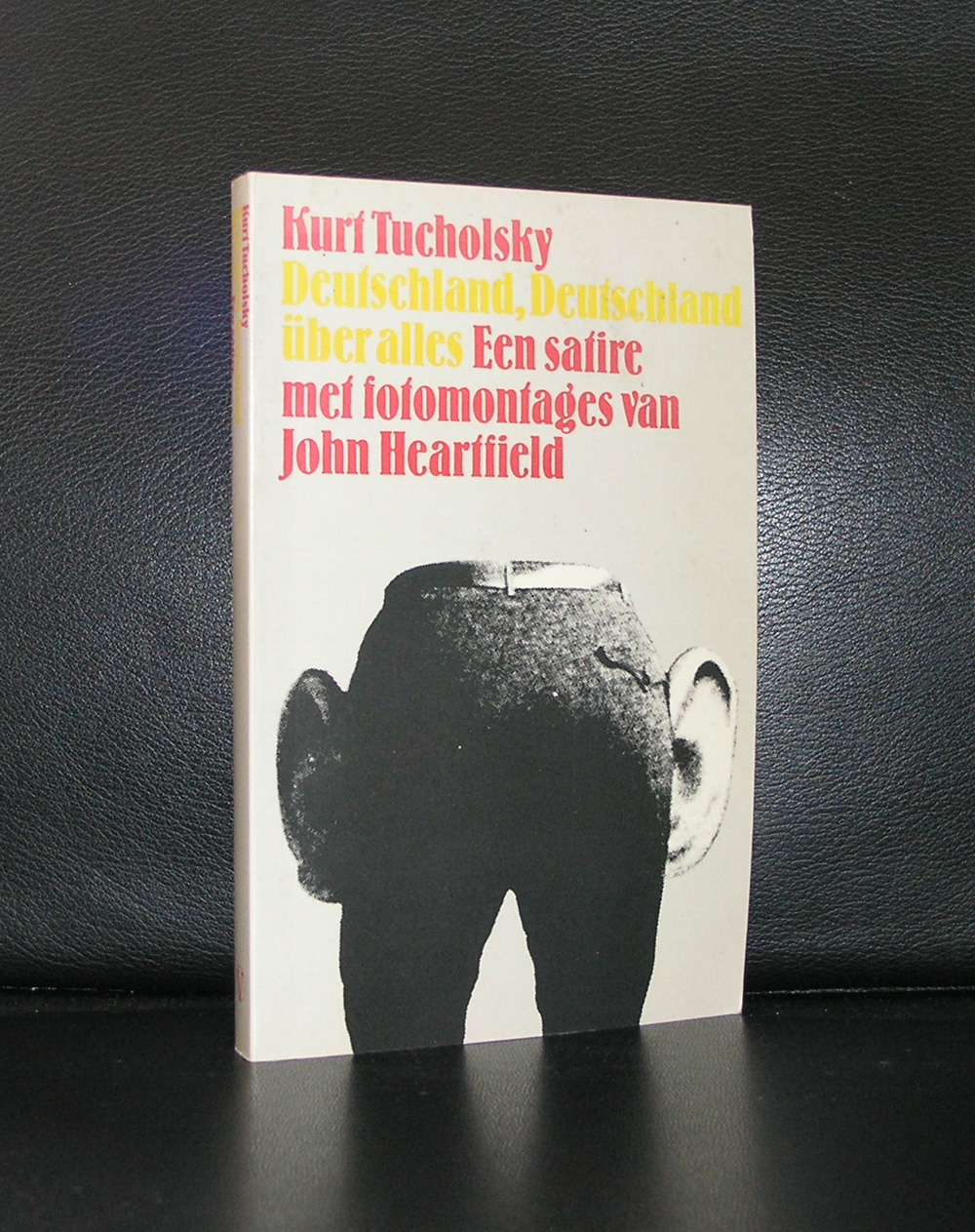

www.ftn-books.com has a few Heartfield titles now available.