The following text was originally published in the New York Times.

Poiret’s achievement is not as visible today as that of Coco Chanel, who built on some of his ideas and discarded others. His fashion house closed in 1929, and he spent his remaining years impoverished. But Poiret was for a while a revolutionary in revolutionary times and also a canny impresario. His radically streamlined, unstructured, often stridently colored clothes freed women from corsets while evoking exotic, non-Western cultures and a fierce disregard for social convention.

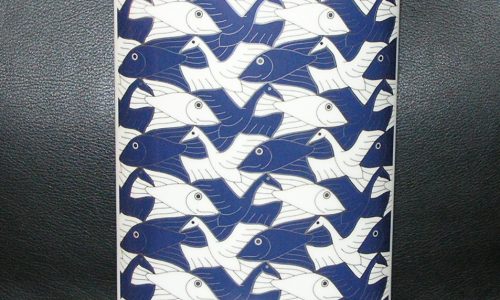

He introduced these corset-free garments in 1906, the year before Picasso committed his decidedly uninhibited (and unstaid) “Demoiselles d’Avignon” to canvas. But with his love of the exotic, his brilliant use of color and pattern, and his penchant for simplified, almost rudimentary form, Poiret most resembles Matisse.

Poiret functioned as a kind of one-man cultural scene. He collected art, gave lavish costume parties and made astute use of the press while laying the groundwork for fashion design as a modern art and a modern business. His clients included Sarah Bernhardt, Nancy Cunard, Isadora Duncan, Colette and Helena Rubinstein. Man Ray photographed Peggy Guggenheim in a Poiret gown and turban. Edward Steichen’s first fashion photographs were taken of models in Poiret’s atelier.

He was the first designer to understand the value of designing for well-known actresses both onstage and off. He was also the first to create his own line of perfume, named Rosine, for his eldest daughter, and the first to open an interior design store, Atelier Martine, named for his second daughter but inspired by the Weiner Werkstätte. His innovations included the chemise, harem pants and pantaloons and the popular lampshade skirt. When he visited the United States in 1913, he found himself called the king of fashion and discovered the underside of modern fashion success: His lampshade skirt was being copied far and wide.

Organized by Harold Koda and Andrew Bolton, who are curator in charge and curator of the Met’s Costume Institute, “Poiret: King of Fashion” conveys quite a bit of his complex genius and his contradictory relationship with modernity. It displays 50 garments on mannequins (by Beyond Design) whose ovoid faces and cryptic features evoke Brancusi and Modigliani. The silk backdrops, which are the work of Jean-Hugues de Chatillon, a French set designer who served as the exhibition’s creative consultant, accent the show’s spaciousness with indelibly Parisian vistas of leafy parks, chic theaters and luxurious drawing rooms. All told you may have the sensation of drifting through a series of extraordinarily beautiful fashion illustrations, an art that Poiret cultivated to his advantage.

Poiret’s liberation of the female body was in part inspired by the gamine build and independent spirit of his wife and muse, Denise, whom he married in 1905. In other ways it was born of necessity. Although he was initiated into the couturier business between 1898 and 1903, working as a designer for Jacques Doucet and then the House of Worth, Poiret never trained in the exacting crafts of couture tailoring or dressmaking.

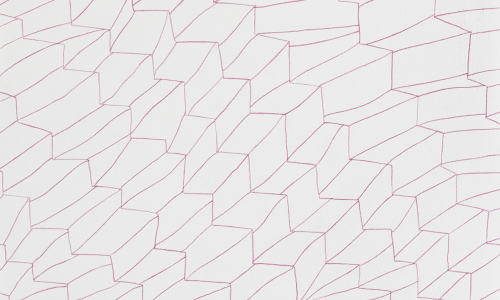

His design ideas began with the flat, rectangle of the fabric itself, as did the Japanese kimonos and North African caftans he admired. They then evolved through draping, not tailoring, into garments with a minimum of seams that pretty much hung from the shoulders.

Poiret drew from a broad range of sources. Early in the show there is a trio of nightgowns, based on the Classical Greek gown known as the chiton, that are precursors to the 1950s negligee and the early 21st-century socialite party dress. To one side of these are two white high-waisted dresses that hark back to the severe yet demure gowns of post-Revolution France, displayed with an Atelier Martine chair that has bubbly hand-painted fabric.

Nearby is evidence of Poiret’s attraction to a more ornate form of non-Western dress: a gauzy harem outfit studded with enormous beads of turquoise celluloid that Denise might have worn to their most famous fete, “The Thousand and Second Night” costume party on June 24, 1911.

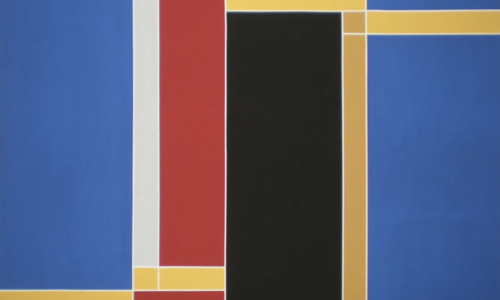

But turn around and you will see a stark simplicity that may take you aback: a gown that resembles nothing so much as a 1960s abstract painting. Wrapped gracefully around a mannequin, it has no sleeves or collar to speak of, just four broad, alternating bands of stylishly darkened red and blue.

Poiret’s best clothes were abstract in a very real sense, with a kind of self-evident structure that is a precursor of Minimalism, as well as of clothing designs as different as those of Rei Kawakubo, Hussein Chalayan and Andrea Zittel. His basic form was a cylinder, with or without sleeves attached. It appeared in his work as early as 1905 in his Révérend Coat embellished with Chinese roundels. The first garment in the show, it is worn over a white, lacy, high-necked, pinch-waisted Edwardian gown, like those Poiret designed at the beginning of his career. The sartorial conflict accents the shock of the newness of his sense of form, structure and color.

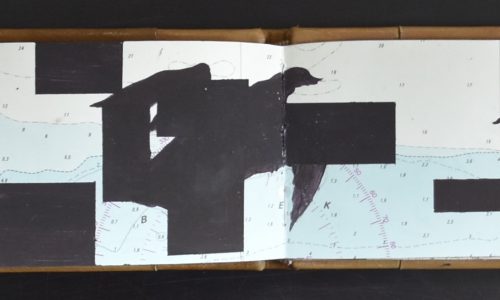

His best known and most audacious designs are a series of full-length columnar opera coats that begin in 1911 and culminate in the 1919 Paris Evening Coat, merely a swath of uncut fabric with a single seam. In a wonderful bit of exhibition magic this Möbius-like feat is demonstrated in a brief digital animation projected on a scrim that then turns transparent, revealing the actual coat behind it.

But even without digital aids you can see how his garments are built, step by step. A day coat began as a black satin jacket based on a Chinese robe. To this he added four strips of cream-colored wool jacquard striped horizontally with thin lines of brown for two cuffs, a simple folded-over collar and a slightly gathered skirt that reaches almost to the floor.

The contrast of fabrics joined in this single form is elegantly harsh, like a combination of Hudson Bay blanket and black tie. A similar contrast is drawn more closely in a jumperlike dress made of gold-lamé twill.

Poiret followed modernity only so far. By the mid 1920s Chanel was designing convenient, understated clothes for women enjoying an increased sense of physical and social freedom in the wake of World War I. But Poiret ignored the shorter skirts and trimmer lines and continued enveloping women in luxurious garments that began to look cumbersome.

the following books on Poiret are available at www.ftn-books.com