Hamilton was a native of London, receiving instruction from the Royal Academy Schools between the years of 1938 and 1940. He then proceeded to study engineering design at a Government Training Centre in 1940 before being employed as a designer for ‘jig and tool’ machinery. In 1946, he returned to the Royal Academy Schools, but was eventually expelled for his failure to grasp the teachings within the painting school (Hamilton, p.10). Despite this setback, he later attended the renowned Slade School of Art from 1948 to 1951.

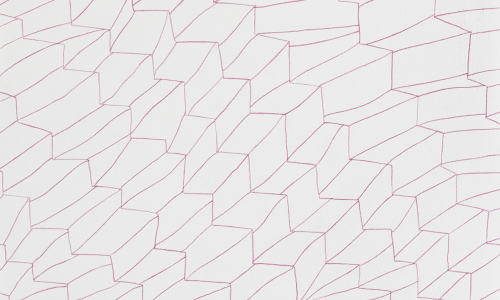

In 1950, Gimpel Fils in London hosted an exhibition showcasing Hamilton’s engravings, inspired by D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s bold 1913 piece, On Growth and Form. The latter had recently been republished in 1942, exerting a profound influence on Hamilton’s nascent work. As a testament to his creative aptitude, he also devised and curated notable exhibitions such as Growth and Form, presented at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1951, and Man, Machine and Motion, held at the Hatton Gallery in Newcastle upon Tyne and again at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1955. Subsequently, he exhibited at the prestigious Hanover Gallery in 1955, and contributed to the seminal event of This is Tomorrow at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1956, where he presented a striking collage piece entitled Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? for the event’s accompanying poster and catalogue. Alongside fellow visionary Victor Pasmore in 1957, he orchestrated an Exhibit at the Hatton Gallery and the Institute of Contemporary Arts.

Notably, Hamilton was a prominent figure of the Independent Group, an assembly of artists and writers founded in the 1950s at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. Their symposiums played a pivotal role in shaping the burgeoning Pop art movement in Britain. Hamilton was also a steadfast proponent of critic Lawrence Alloway’s widely acclaimed thesis concerning the ‘fine/pop art continuum’. In his own interpretation, Hamilton viewed this concept as a means of establishing the principle of equality in art – proposing that there exists no hierarchical ranking of artistic value. To him, Elvis held the same standing as artists like Picasso, occupying two distinct ends of the artistic continuum. Furthermore, Hamilton strongly maintained that television deserved as much recognition and influence as the likes of New York Abstract Expressionism.

Hamilton served as an instructor at the London Central School of Arts and Crafts and the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, but ultimately retired from full-time teaching in 1966. He also made a typographic rendition of Duchamp’s Green Box, which was published in 1960. Working closely with Duchamp, Hamilton reconstructed The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (Tate Gallery T02011) in 1965-6. In the 1980s, Hamilton delved into incorporating technology into his artwork. He has had a successful career as a print-maker, and in 1983 he received the prestigious World Print Council Award. In 1991, Hamilton tied the knot with fellow artist Rita Donagh. Retrospective exhibitions of his work have been on display at the Hanover Gallery in 1964, the Tate Gallery in 1970 and 1992, and internationally. In fact, Hamilton represented Britain at the esteemed 1993 Venice Biennale.

www.ftn-books.com has several Richard Hamilton titles available. Among them the spectacular Stedelijk Museum catalog.