Upon entering the living room, sipping coffee in the kitchen, and wandering through the studio, I am aware of what is to come. It all halts at the defiant table. I peruse books on Thierry De Cordier, Berlinde De Bruyckere, Arnulf Rainer, and immerse myself in the seventeenth-century Chinese landscape painter Wang Hui. I extend the moment, avoiding looking just yet. I feel reluctance to turn around and face the new canvases. I have seen a few before, in an earlier phase, almost two years ago. I have an inkling of what to expect.

It feels like entering a mortuary: You want to go inside, but you also know it will be confronting. So you delay as long as possible. Seeing is knowing. And the mind still says ‘no’. No, to the overly explicit wound that strikes at womanhood. No, to the pain and sadness that speaks through these paintings. I recall the irritation I felt last time at the physical embodiment of soft red, the hairy skin, blue-veined. But wasn’t it the Jan Hoet we both admired who suggested that doubt and resistance are the best guides when it comes to art? ii If I am to be honest, that is probably the main reason why I am back in the studio.

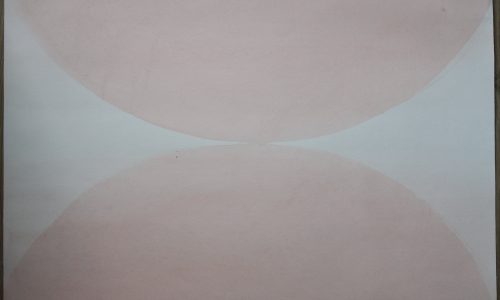

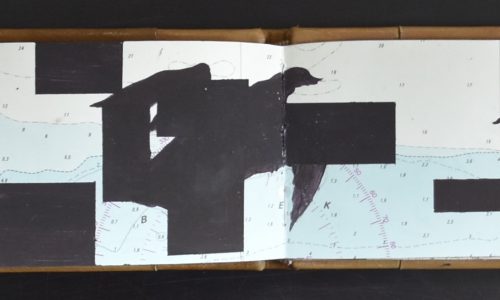

Hans himself calls the paintings Mental Landscapes. “Nothing mental,” I initially think, as once again I see mainly skin, blood red, soft pink, blue-purple veined. A pattern of ribs, and that confronting wound, which also explicitly represents a vagina. While we talk and gaze at the first canvas, I no longer only see skin and genitals in the red, gradually I also discern a massive curtain: a murky veil or dark celestial vault that tears apart. The whole thing drips with paint, floating above a tranquil landscape, a tiny world. But at the bottom of the canvas, in soft white and Prussian blue, light shines, there lies hope. www.ftn-books.com has the OCHTENDLICHT publication now for sale.