The best way to introduce Claudia Kölgen is to use a text I found on the internet page by Michael Gibbs.

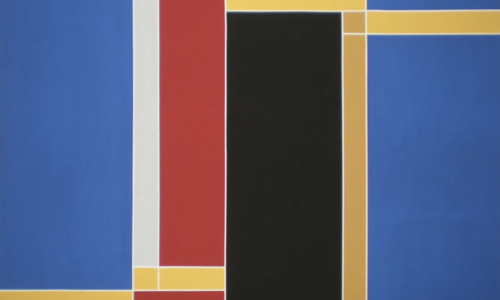

Light, space, image, screen and language are the elements that form Claudia Kölgen’s artistic practice. Yet rather than dealing with these elements in a formalistic sense, she employs them in a poetic, almost abstract, metaphysical way, drawing attention to the specificity not of the medium but of the picture, the object, as well as the specific way these are perceived.

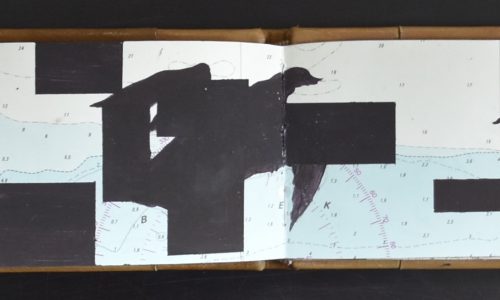

Her book objects are beautifully crafted, and extend our sense of what a book means – a sequence of identical pages in a closed form that invites an opening, a filigree of strands conducting the charge of meaning to a reader/viewer, a breath of air whispered between the leaves. Stéphane Mallarmé, who once compared the printed page to an elusive white butterfly would certainly have approved of Claudia Kölgen’s books. Mallarmé described the book as a ‘spiritual instrument’, but whereas he envisaged a Total Book containing ‘everything that exists’, Claudia Kölgen reduces the book to its essence. Her infra-red photograph of a still-life arrangement of open and closed books allows us to conceive of the book as a warm comforting object, as a body.The page of a book is analogous to a screen, so it should come as no surprise to learn that Claudia Kölgen has worked extensively with film and film installation. The first time I ever saw her work was at a group exhibition of film installations in a decrepit building on the Warmoesstraat in Amsterdam. Claudia’s work stood out for the simple economy of its means and its utter effectiveness. The piece was entitled ‘Choreographie der Bilder’ and consisted of two loop films of candle flames photographed in slow motion projected through a board (with a grid of circular holes cut out of it) onto a double screen cantilevered like the open cover of a book. The random, organic tongues of flame thus became transformed into a computer-like grid of dancing circular spots of light. In one cinematic jump we are carried from the primeval to the electronic age.

A similar breadth and economy is achieved in her previous film installation ‘Lighthouse’ in which a vertical beam of light is rotated from a central, beacon-like axis around the walls of the space, which includes a sheet of copper and a glass frame. At the same time a film is being projected, which we occasionally get glimpses of. A lighthouse usually projects beam of light into the distance – it is meant to be seen from afar, but Claudia Kölgen’s lighthouse is just that: a light house, an enclosed space whose internal contours and surfaces are made visible reflectively, as a sign of introversion. The continuously moving beam of light intersecting with the film being projected challenges the spectator’s sense of space as something static. The viewer’s gaze becomes mobilized, disoriented.

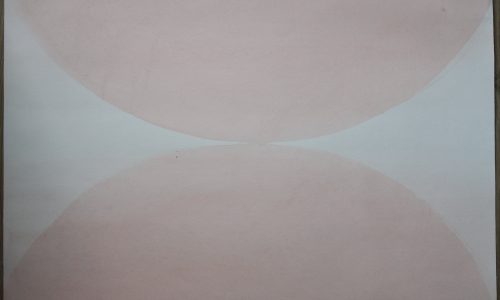

The interference of one space with another is also the theme of her film ‘Ricercar’. The title is a musical term meaning to start again anew, and this is interpreted by the cello music on the sound track. The film is a journey through an abandoned industrial building, but it is really two films in one, since the centre of the frame is occupied by another moving image taken from a second camera placed at a right angle to the first, so that what we see are two views literally interfering with one another in a continual, vertiginous process of change. What we are left with is a vision of the pure relativity of space. This is not the modernist, fractured space of cubism, but a completely conditioned, reductive sense of space – one that offers not progress but recurrence. And this is where the element of time comes in – the endless, repetitive time of the film loop, or the steady revolving of a tower, or the pace of walking. Time is not a simultaneity (as in the modernist vision) but an ordered, self-effacing sequence.

Kölgen’s film ‘Wende’ (Turn) epitomises the dualities and dialectics that inform her work. The undulations of a sandy beach are filmed in positive and negative and overlaid with enlarged typewritten letters. On the sound track we hear layers of random spoken words which gradually disintegrate into phonemes and consonants. Language becomes reduced to what Barthes refers to as the ‘grain’ of the voice/text, a polysemy without origin or end.

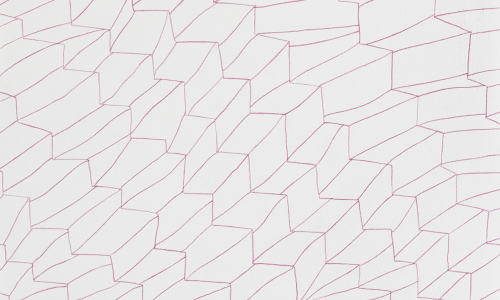

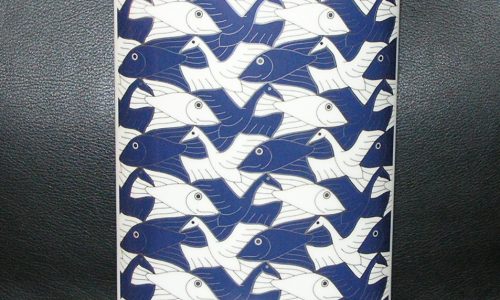

The grid of circular holes used in her film installation recurs in her recent photoworks. In one piece, circular pieces of colour film negatives are sandwiched between two sheets of perspex and lit from behind – we cannot make out what is depicted; the images remain imaginary, waiting as it were to be realized through the action of light and chemicals. Kölgen’s screens are at once opaque and transparent – their grid structure makes them indices of infinity, like so many zeros, but we are reminded too of the mental screen that each of us possesses which filters everything that we perceive. Whether we call this screen rationality or the unconscious, it is always resisted by the immediacy of lived experience and by the knowledge (or at least the suspicion) that our perceptions are more than just fleeting shadows on the walls of a cave.

Photographs are traces of experience, not the experience itself; their logic is that of an absent presence, of what Barthes calls a ‘having-been-there’. Yet the photograph is also a type of icon, a model of that which is represented. As André Bazin has written, ‘The photographic image is the object itself, the object freed from the conditions of time and space that govern it. No matter how fuzzy, distorted, or discoloured, no matter how lacking in documentary value the image may be, it shares, by virtue of the very process of its becoming, the being of the model of which it is the reproduction; it is the model.’ The images that appear in Kölgen’s photoworks – clouds, a room, a figure on a beach – are not documents; they need no captions to explain them. They are models within a larger model having to do with seeing and not seeing. Natural light is combined with artificial light, reality with construction. We are no longer certain of what we see, since we are made conscious of the very determinants of seeing – the screen separating blindness and insight, the spectacle and the spectator.

Michael Gibbs

February 1989

Now that she is introduced properly I like you to know that I have added 2 important publications by Kölgen. The one that stands out is the HEFTIG ALS EEN STORMWIND. Published in an edition of 10 copies. Each numbered and signed. Package contains 20 cigarettes all printed with different texts by Claudi Kölgen , each package is signed and numbered

available at www.ftn-books.com