Gustavo de Maeztu was a unique and enigmatic artist, known for his dispersion and individuality. He was both lyrical and romantic, yet controversial, characterized by his passionate and sensitive creations. It was difficult to categorize his work into a single movement, as he actively avoided conforming to classifications and constantly strayed from his own identity. His life was a constant push forward, but also a series of backward moves, leading him to the brink of impressions and precise moments. This made him a captivating and unparalleled figure, impossible to classify due to his quest to find personal explanations that were disconnected from reality.

During the height of his creative period, from 1910 to 1925, De Maeztu crafted a large body of work that revolved around merging personal aspirations, interior aesthetic formulation, and his identification with Spain’s intellectual reflection. This resulted in an ambivalent artistic output that was both intimate and social, lyrical and epic, restrained and overwhelming, and at times, both melancholy and hopeful. This magical duality was simultaneously his downfall and his eternal legacy.

Two recurring themes characterized his work during this period: man and woman. His depictions of men were often melancholy, deep in thought and occupied with matters that were beyond human understanding. This hermeticism and subsequent sense of alienation only added to their mystery. On the other hand, his female figures were powerful, voluptuous, and sensual, with an air of elegant sophistication that seamlessly integrated elements of folk boisterousness with aristocratic grace. His female figures were often adorned with a magnificent display of vibrant colors, reminiscent of the shimmering tones of ceramic.

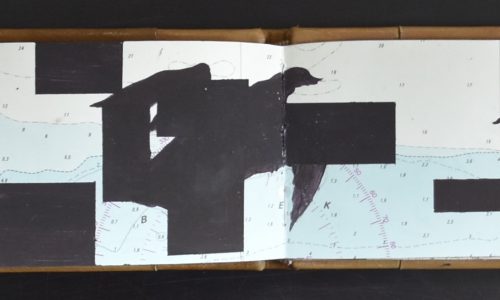

With a strong literary essence in his paintings, Gustavo de Maeztu skillfully used the diptych and triptych techniques in his compositions to tell a story. This can be seen in his paintings, such as The Samaritan Women (Museo Gustavo de Maeztu, Estella-Lizarra) and The Women of the Sea. Through these techniques, he was able to bring life to his paintings and further enhance the enigmatic complexity and linguistic dynamism of his work, making him a true master of his craft.

The artist creates from the dualistic language of imagery, using it as a dreaming vessel that contains deeper symbolism. “The Samaritan Women” portrays women from a despondent region of Castilla, heavily burdened but determined, showing no signs of weariness as they confront their destiny. In contrast, “The Women of the Sea” reveals a stark and ominous landscape, with women who do not wear a smile and have no prospects for the future. Their only desire is for the safe return of their loved ones, and the endless wait is reflected in their somber countenances. These women are monumental in their depiction, exerting a greater force than the very architecture of the houses that make up the serene backdrop, particularly against the languid waters that mirror their forms. The bridge and the faces are etched with anguish, with eyes that search, inquire, and scan the distance in an attempt to understand, yet only being met with endless waiting. The artist’s treatment of the figures resembles that of a sculptor, emphasizing the notion that they are massive paintings come to life. His close friend and art critic, Juan de la Encina, who was captivated by this piece, marveled at the “iridescent skirt, with a dominant shade of violet, on the reclining woman or the one resting on her lap (though we suspect it is more of a lap), adorned in a crimson gown that seems to ignite the entire painting.”

www.ftn-books.com has one title on Maeztu now available